When Harvard University’s Making Caring Common Project released their report, “The Children We Mean to Raise: The Real Messages Adults Are Sending About Values,” the study found that many kids value academic achievement and individual happiness over caring for others. In the report, the authors explained that the children’s values reflected what they believe the adults in their lives value.

We live in an age in which we are more and more connected by technology, but this connectedness doesn’t seem “to be translating to genuine concern for the world and one another.” Research from the University of Michigan has shown that college kids today are nearly 40% less empathetic than they were 30 to 40 years ago.

In the wake of these disturbing study results, the Making Caring Common Project and the Ashoka Empathy Initiative created a set of recommendations for teaching empathy to children.

Empathy goes beyond being able to see another person’s point of view, according to Rick Weissbourd, the co-director of the Making Caring Common Project. He points out that sales people, politicians, actors and marketers are able to do this kind of “perspective-taking” in pursuit of their professional goals. Con men and women use this ability to manipulate their victims for personal gain. In order to be truly empathetic, children need to learn more than simple perspective-taking; they need to know how to value, respect and understand another person’s views, even when they don’t agree with them. Empathy, Mr. Weissbourd argues, is a function of both compassion and of seeing from another person’s perspective; and it is the key to preventing bullying and other forms of cruelty and discrimination.

To that end, the project offers these five suggestions for developing empathy in children:

1. Empathize with your child and model how to feel compassion for others.

Kids develop these qualities by watching us and experiencing our empathy for them. When we show that we truly know our children by understanding and reacting to their emotional needs, exhibiting interest and involvement in their lives, and respecting their personalities, they feel valued. Children who feel valued are more likely to value others and demonstrate respect for their needs. When we treat other people like they matter, our kids notice, and are more likely to emulate our acts of caring and compassion.

2. Make caring for others a priority and set high ethical expectations.

Kids need to know that we are not simply paying lip service to empathy, that we show caring and compassion in our everyday lives. Rather than say, “The most important thing is that you are happy,” try: “The most important thing is that you’re kind and that you are happy.” Prioritize caring when you talk about others, and help your child understand that the world does not revolve around them or their needs.

3. Provide opportunities for children to practice.

Empathy, like other emotional skills, requires repetition to become second nature. Hold family meetings and involve kids by challenging them to listen to and respect others’ perspectives. Ask children about conflicts at school and help them reflect on their classmates’ experiences. If another child is unpopular or having social problems, talk about how that child may be feeling about the situation, and ask your child how he or she may be able help.

4. Expand your child’s circle of concern.

It’s not hard for kids to empathize with their immediate family and close friends, but it can be a real challenge to understand and feel for people outside of that circle. You can help your child expand their circle by “zooming in and zooming out”; listening carefully to a particular person and then pulling back to take in multiple perspectives. Encourage your child to talk about and speculate on the feelings of people who are particularly vulnerable or in need. Talk about how those people could be helped and comforted.

5. Help children develop self-control and manage feelings effectively.

Even when kids feel empathy for others, societal pressures and prejudices can block their ability to express their concern. When kids are angry with each other over a perceived slight, for example, it can be a real challenge for them to engage their sense of empathy. Encourage kids to name those stereotypes and prejudices, and to talk about their anger, envy, shame and other negative emotions. Model conflict resolution and anger management in your own actions, and let your kids see you work through challenging feelings in your own life.

Educators will tell you that a classroom full of empathetic kids simply runs more smoothly than one filled with even the happiest group of self-serving children. Similarly, family life is more harmonious when siblings are able feel for each other and put the needs of others ahead of individual happiness. If a classroom or a family full of caring children makes for a more peaceful and cooperative learning environment, just imagine what we could accomplish in a world populated by such children.

This column was adapted from an article by Jessica Lahey, an educator, writer, and speaker. She writes about parenting and education.

Talking About School

The school year is now in “full swing.” So think about the school-related dialog you engage in with your children about school throughout the school year. To make those conversations more meaningful, gather increased information, encourage and nurture self-responsibility, and build positive relationships with your children, consider the following do’s and don’ts.

Do listen, listen, listen. When your child begins talking about school, put down what you were doing, resist the urge to multitask, turn and face your child, give strong eye contact, lean forward, and pay attention. Let your body language communicate “I am here for you. I am present. I care what you have to say, I am interested.”

Don’t judge what your children are saying. The instant you judge with “That’s a good/bad idea,” “How could you have done that?” “You should have done this . . .” you are inviting an abrupt end to the conversation. Judging sends a “Big Me/Little You” message. A judge by definition is above the person being judged. Children do not like being in that position and will give you less information in the future.

Don’t say “I was bad in math, too.” First of all, this statement announces that you agree that your child is bad in math. Your child is not bad in math. She is simply learning fractions slowly right now. Second, this sentence invites her to view her math ability as hereditary. This can quickly transfer into a dead-end belief: “Being bad in math runs in the family.”

Do invite goal setting. Help your child set goals for the year, week, or even the day on occasion. Also show them that when they have a goal, it requires action steps to reach it. For instance, if their goal is to learn their multiplication tables, what do they need to do to get there? 1. Make flash cards. 2. Practice with 2’s and 3’s by myself. 3. Have someone else practice with me. 4. Do a timed practice test. 4. Move on to the 4’s and 5’s. And so on.

Don’t ask “Do you have any homework?” This question is often the first words out of a parent’s mouth when they greet their children after school. “It’s good to see you. Hope you had a great day” is a more inviting, nurturing greeting. Then a little later, you can ask about homework.

Do praise effort over intelligence. When parents predominately praise intelligence, as in “You’re so smart. You have a great brain there,” children come to see intelligence as a fixed commodity. They think people are smart or not and there is not much anyone can do about it. Through effort, intelligence can be increased. To praise effort, say, “You worked on that Spanish until you learned to use all of the 15 color words,” or “You sure are working hard on that term paper/book report/science project. Looks like you’re going to have it done on time.”

Do invite your children to share what they have learned with you. “How about teaching me how to do that?” “Is there something you learned in school today that I might not know? I’d like to hear about it.” The fastest way to lock in learning is to teach a concept or skill to someone else. Have your children move their learning into their long-term memory by teaching it to you.

Do ask questions that require more than a one-word answer. “How was school today?” is going to get you the often-spoken “Fine.” “If you could change one thing about today, what would it be?” will likely be the start of a meaningful conversation. “Tell me about the most interesting/surprising/humorous thing that happened today” will invite your children to enter into an expanded dialog.

Do not say “If you get in trouble at school, you’ll be in trouble at home, too.” Having this conversation before inappropriate behavior has occurred sends the silent message that you expect inappropriate behavior to occur. In addition, it is applying double jeopardy. If your child is held accountable by the school personnel, you do not need to pile on extra consequences.

Do not say “This year will be a lot harder than last year” or “That’s going to be a tough class.” Sending ominous warnings creates an expectation of harder and tougher in your child’s mind. Do you really want your child going into the new school year thinking the class/grade/teacher will be hard? If it is hard, they will figure that out soon enough.

Do inquire “How did you choose to BE today?” instead of “What did you DO today?” Over time, this question helps children understand that they do indeed choose how to BE. They become conscious that their attitude and demeanor are controllable, and that they, themselves, are the controller.

Pick a couple of these suggestions to implement this week. You will know which ones.

This column was adapted fro an article by Chick Moorman and Thomas Haller, two of the world’s foremost authorities on raising responsible, caring, confident children. Their websites are: www.thomashaller.com or www.chickmoorman.com.

Social Competence

Parents who want their kids to succeed have been known to play Mozart in the nursery and quiz their preschoolers with flash cards, but a new study suggests these parents might want to go back to the basics by teaching children to share and take turns.

Kindergarteners with strong social and emotional skills were more likely than their peers to succeed academically and professionally, according to a 20-year study that followed more than 750 children until age 25.

Youngsters whose kindergarten teachers gave them the highest scores on “social competence” were more likely than other kids to graduate high school on time, earn a college degree, and hold full-time jobs.

Social competence involves more than making friends, according to the study, published in the American Journal of Public Health.

Teachers rated kids on the ability to cooperate, resolve conflicts, listen to others’ points of view, give suggestions without being bossy, and other social skills.

Kids with weaker social skills were more likely to develop substance abuse problems, be unemployed, smoke pot, get arrested, live in public housing, or receive public assistance, according to the study, which included children from low-income neighborhoods in Nashville; Seattle; Durham, N.C.; and central Pennsylvania.

For some measures of adult success, good social skills appeared to be more important than academic ability, said co-author Damon Jones, a senior research associate at Pennsylvania State University. Likewise, social competence often proved to be a better predictor than race, sex, or family income.

Children with poor social skills in kindergarten are by no means a lost cause, pediatrician Dina Lieser said. The study provides a hopeful message because it’s possible to improve social skills throughout childhood, said Lieser, chairwoman of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Council on Early Childhood, who wasn’t involved in the study.

A growing number of studies point to the importance of early childhood experiences in shaping the brain and later behavior. A 2011 study found that people who showed more self-control as preschoolers were healthier and wealthier by age 32, even after researchers considered influential factors such as IQ and social class.

A person’s social development starts at birth. Even tiny babies begin to interact with the people around them. They respond to voices. They cry to let caregivers know they need something. They make eye contact and smile at those who feed them, hold them, or play with them.

Adults and older children, intentionally or not, are models for young children of how to behave with other people. In fact, a great deal of children’s social behavior is influenced by what they observe other people doing.

Most children’s social skills increase rapidly during the preschool years. It is important to keep in mind that children of the same age may not have the same levels of social competence. Research shows that children have distinct personalities and temperaments from birth.

Relationships within the family also affect a child’s social behavior. Behavior that is appropriate or effective in one culture may be less so in another culture. Therefore, children from diverse cultural and family backgrounds thus may need help in bridging their differences and in finding ways to learn from and enjoy one another. Teachers can help by creating classroom communities that are open, honest, and accepting of differences.

Much research suggests that pretend play can contribute to young children’s social and intellectual development. When children pretend to be someone or something else, they practice taking points of view other than their own. When they pretend together, children often take turns and make “deals” and decisions cooperatively. Such findings suggest that children in early childhood programs ought to have regular opportunities for social play and pretend play. Teachers can observe and monitor the children’s interactions.

The Social Attributes Checklist* below was created to help check to see whether a child’s social competence is developing well. The intent of this checklist is not to prescribe correct social behavior but rather to help teachers and parents observe, understand, and support children whose social skills are still forming. The list is based on research on elements of young children’s social competence and on studies comparing behavior of well-liked children with that of children who are not as well liked.

Many of the attributes included in the checklist indicate adequate social growth if they are usually true of the child. Illness, fatigue, orother stressors can cause short-term variations in a child’s apparent social competence. Such difficulties may last only a few days. Teachers or parents will want to assess each child based on their frequent direct contact with the child, and observation of the child in a variety of situations.

If a child seems to have most of the traits in the checklist, then he orshe is not likely to need special help to outgrow occasional difficulties. On the other hand, a child who shows few of the traits on the list might benefit from adult-initiated strategies to help build more satisfying relationships with other children.

I. Individual Attributes

The child:

▪ Is usually in a positive mood.

▪ Usually comes to the program willingly.

▪ Usually copes with rebuffs or other disappointments adequately.

▪ Shows interest in others.

▪ Shows the capacity to empathize.

▪ Displays the capacity for humor.

▪ Does not seem to be acutely lonely.

II. Social Skills Attributes

The child usually:

▪ Interacts nonverbally with other children with smiles, waves, nods, etc.

▪ Expects a positive response when approaching others.

▪ Expresses wishes and preferences clearly; gives reasons for actions and positions.

▪ Asserts own rights and needs appropriately.

▪ Is not easily intimidated by bullies.

▪ Expresses frustrations and anger effectively, without escalating disagreements or harming others.

▪ Gains access to ongoing groups at play and work.

▪ Enters ongoing discussion on a topic; makes relevant contributions to ongoing activities.

▪ Takes turns fairly easily.

▪ Has positive relationships with one or two peers; shows the capacity to really care about them and miss them if they are absent.

▪ Has “give-and-take” exchanges of information, feedback, or materials with others.

▪ Negotiates and compromises with others appropriately.

▪ Is able to maintain friendship with one or more peers, even after disagreements.

▪ Does not draw inappropriate attention to self.

▪ Accepts and enjoys peers and adults who have special needs.

▪ Accepts and enjoys peers and adults who belong to ethnic groups other than his or her own.

III. Peer Relationship Attributes

The child:

▪ Is usually accepted versus neglected or rejected by other children.

▪ Is usually respected rather than feared or avoided by other children.

▪ Is sometimes invited by other children to join them in play, friendship, and work.

▪ Is named by other children as someone they are friends with or like to play and work with.

IV. Adult Relationship Attributes

▪ Is not excessively dependent on adults.

▪ Shows appropriate response to new adults, as opposed to extreme fearfulness or indiscriminate approach.

*(Adapted (with some additions) from McClellan & Katz (2001) Assessing Young Children’s Social Competence and McClellan & Katz (1993), Young Children’s Social Development: A Checklist.)

10 Tips for Raising Unspoiled Kids

The following column is adapted from an article by Dr. Sheryl Zeigler, a counselor and therapist at the Child and Family Therapy Clinic in Denver, Colorado. In her practice she often sees middle and upper class families struggling with wanting to raise “grateful and unspoiled children,” despite having a comfortable lifestyle, going on nice vacations, having lovely homes; and owning the latest gadgets, toys and cars. These parents ask if it is really possible, and the answer is “Yes, but you are going to have to work at it.” She calls it intentional parenting and it takes self discipline to pull it off.

So, here is her list of the top 10 things around which you need to have clarity and consistent follow through in order to raise unspoiled children whether you are wealthy or not.

1. Say no. Practice delayed gratification and simply not always giving your children what they want, even if you can easily afford it.

2. Expect gratitude. Go beyond teaching your child to say please and thank you. Also teach them eye contact, a proper hand shake, affection and appreciation for the kind and generous things that are said and given to them. If this does not happen, have them return the gift (either to the person or to you for safe keeping) and explain that they aren’t yet ready to receive such a gift.

3. Practice altruism yourself. Donate clothes and toys to those in need (not just to your neighbors when it’s easy and they have younger children!) and have your kids be a part of that process. Do this regularly as a family and sort through, package and deliver the goods together so the kids really see where their things are going. Do this often and not just around the holidays.

4. Be mindful of the company you keep. Be sure family or friends you are spending significant time with have similar values to yours, otherwise you are going to feel defeated after a while.

5. Write thank you cards. Yes, handwritten on paper with a pen! Kids these days generally have shorter attention spans, are easily distracted and aren’t taught to take careful time and attention to express their appreciation. This simple yet important act can go a long way as a skill to teach expression of feelings and thoughtfulness.

6. Don’t catch every fall. Practice natural consequences from an early age — share some of your own experiences and teach them lessons such as “life is not fair.” In addition, don’t over-protect them from disappointments. You have to really understand and believe that failing and falling are a part of successful childhood development.

7. Resist the urge to buy multiples of things. Just because you can doesn’t mean that you should! Don’t buy four American Girl Dolls—buy just one and have your child love and appreciate what they have.

8. Talk to their grandparents and explain your intentions to them. Share with them your desires to have respectful, appreciative, kind and responsible children and the ways in which you are going to achieve that goal. You will need their help in doing this if they are like most grandparents who want to spoil their grandkids! Ask them to spoil them with love, time, affection and attention—not toys, treats and money.

9. Teach them the value of money. Have your child manage their money through saving, giving to charity/others, and then spending. If you do this from an early age you are truly setting a foundation of responsible wealth management.

10. Share your story. Last but not least, you should tell your kids the legacy of your family’s good fortune. If you come from wealth tell the story of how that was earned and created. If you are self-made, tell that story too—just don’t forget that “giving your kids everything that you didn’t have” is not always a good thing. There is probably a lot that you learned along the way by stumbling to make you the person you are today.

And at the end of the day, if you have a spoiled child—one who relentlessly nags, cries and throws a huge fit when they do not get what they want—you only have yourself to blame! Stop giving in and start applying most if not all of these values and approaches. You will have greater enjoyment in being a parent, your child will be happier and better adjusted and there will be greater peace and love in your home. And that is something money cannot buy.

Former Foster Child Sworn In As Youngest Volunteer

Sheree Bain, a former foster child, was recently sworn in as the youngest CASA volunteer for Murray/Whitfield CASA, located in Dalton, GA!

Sheree entered foster care in Georgia when she was very young and was adopted as a small child. Once she became a teenager, her adoptive parents surrendered their parental rights and she returned to foster care. Sheree recruited her own adoptive family and was adopted again as a teenager. She remains very connected today to her adoptive family.

Sheree called her former DFCS (Department of Family & Children Services) case manager, Lamar Wadsworth, a few months back and told him that she wanted to find some way to give back and help children in foster care. He suggested that she look into becoming a CASA volunteer – and as they say, the rest is history!

Chelsea Moser of Murray/Whitfield CASA commented that the program is “delighted to be the beneficiaries of the eagerness with which [Sheree] has approached giving

Chelsea Moser (Murray/Whitfield CASA), The Honorable Connie Blaylock, Sheree Bain & Lamar Wadsworth (Polk Co. DFCS) at Sheree’s swearing-in as a CASA volunteer

back to foster children. Sheree brings a unique perspective to our program and a deep empathy to the children we serve. Her inspiring success as well as her tremendous energy and heart for serving foster children have already been a source of motivation for the rest of us. We are grateful and excited to have her on board, and to learn more from her!”

In addition to being committed to helping foster children, Sheree is a devoted wife to Kory, a deputy sheriff in Whitfield County, and their two young boys.

Sheree is a very inspiring example of someone who has overcome a difficult childhood and is now giving back to help others in her community!

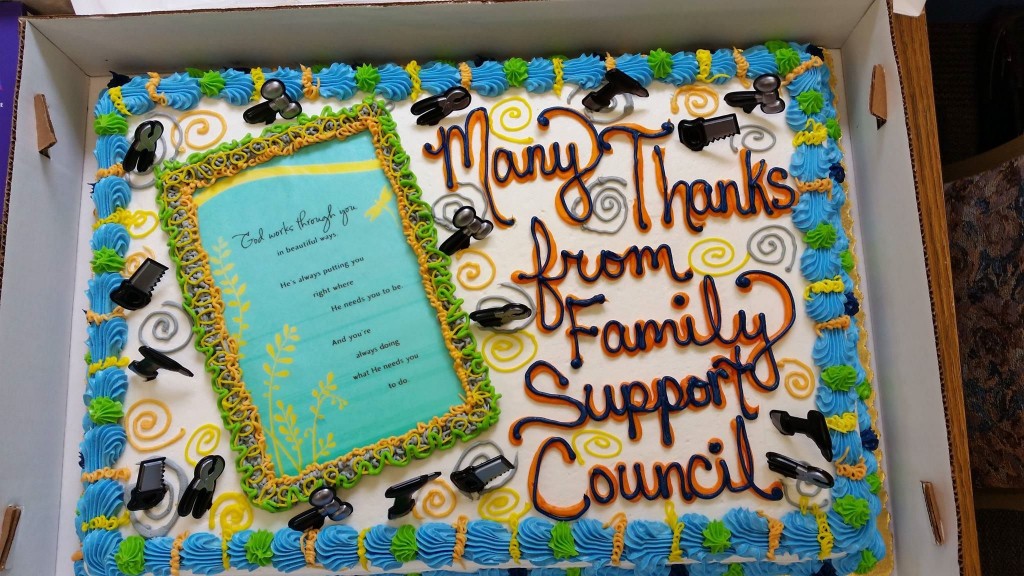

A message of thanks from FSC Executive Director Holly Rice

Mother Teresa once said “I want you to be concerned about your next door neighbor. Do you know your next door neighbor?” FSC has the good fortune to be neighbors with Shaw Plant 6 whose management team and maintenance crew have taken Mother Teresa’s message to heart. There have been countless times when Shaw Plant 6 has responded to maintenance issues that have arisen at our building, allowing us to focus funding and energy on our efforts to prevent child abuse and neglect. Many thanks to these individuals who are concerned about their neighbors and their community!

Heat Entrapment

Warmer weather is here and we have already heard of the seemingly inevitable news that children have died from heat stroke while trapped in a vehicle.

It has been known to happen as early as February if the temperature is warm, but typically around the middle or end of March we hear of the first event of the year – a disturbing, horrific incident of an infant or toddler dying from being trapped in a sweltering car.

Since 1998, the annual average of juvenile deaths in cars has been 38, according to the Department of Earth and Climate Science. Since 1998, there have been more than 700 juvenile deaths triggered by hyperthermia, or heat stroke; more than 70% of these are under the age of two and two thirds under the age of 6. Here are some other statistics:

• Child vehicular heat stroke deaths for 2014: 31

• Child vehicular heat stroke deaths for 2013: 44

• Child vehicular heat stroke deaths for 2012: 33

• Child vehicular heat stroke deaths for 2011: 33

• Child vehicular heat stroke deaths for 2010: 49

• Child vehicular heat stroke deaths for 2009: 33

Parents running quick errands may think their cars will remain cool; but even on mild days, temperatures inside vehicles can rise to dangerous levels in just minutes. A young child’s core body temperature can increase three to five times faster than that of an adult, causing permanent injury and even death.

The family car parked in the driveway can also be dangerous. Unlocked cars pose serious risks to children who are naturally curious and often lack fear. Once they crawl in, young children often don’t have the developmental capability to get out. About one-third of heat-related deaths occur when children crawl into unlocked cars while playing and become trapped.

Here are some tips on protecting your children:

Heat:

•Never leave your child in an unattended car, even with the windows down, even for a few minutes. It takes just 10 minutes for the temperature in a car to go up 20 degrees. Cracking the windows or parking in the shade are not sufficient safeguards.

•Check to make sure all children leave the vehicle when you reach your destination, particularly when loading and unloading. Don’t overlook sleeping infants.

•Make sure you check the temperature of the child safety seat surface and safety belt buckles before restraining your children in the car.

•Use a light covering to shade the seat of your parked car. Consider using windshield shades in front and back windows.

Trunk Entrapment:

•Teach children not to play in or around cars.

•Keep car keys out of reach and sight.

•Always lock car doors and trunks, especially when parked in the driveway or near the home.

•Keep the rear fold-down seats closed to help prevent kids from getting into the trunk from inside the car.

•Be wary of child-resistant locks. Teach older children how to disable the driver’s door locks if they unintentionally become entrapped in a motor vehicle.

•Contact your automobile dealership about getting your vehicle retrofitted with a trunk release mechanism.

•If your child gets locked inside a car, get him out and dial 9-1-1 or your local emergency number immediately.

Let’s make summer a fun and happy time with none of these tragedies of children being left unattended in parked cars.

Being Fair

As parents, we’ve all heard our children tell us, “That’s not fair!” So…

Do you try to make sure both pieces of cake are exactly the same size?

Do you count the Christmas and other gifts so each child gets the same amount?

Do you let your teen attend events that her friends attend even if you have misgivings?

If so, you’re attempting to be fair, and it won’t work. Here’s why.

1. You can cut the cake as evenly as possible, measure how full the glasses are, and count out the exact number of Easter goodies placed in each basket. Someone is likely to see it as unequal anyway.

2. It requires a lot of energy to even things out. Measuring, counting and comparing are a waste of time, effort, and energy.

3. By making sure that everything is fair, you set yourself up for regular complaints and verbal hassles.

4. Attempts to be fair contribute to sibling rivalry. “He got more than I did.” This pits child against child.

5. You are setting yourself up for manipulation. Children can use your desire to be fair to invite guilt and shame.

6. Treating each child equally does not meet the needs of the specific person. If one requires eyeglasses and another needs a special diet, do you give both children glasses and put each one on the same diet? Of course not. Different kids have different needs. Think equity, not equality.

7. Attempting to make things fair for your children helps them develop a dysfunctional life myth that everything in life should be fair. While most child development experts don’t advocate telling children, “Life isn’t fair,” they don’t advocate teaching them through your behaviors that life ought to be fair either.

8. To allow children to expect that everything should be fair sets them up for recurring frustration and disappointment.

9. Striving to be fair encourages feelings of entitlement in children. It contributes to their learning to expect to get what they want when they want it.

10. When your teen says, “It’s not fair. Everyone else gets to go. Why not me?”, the adult is required to do the thinking. You end up doing the thinking and the convincing. Say, “Convince me why you should go,” to require the child to do the thinking.

Next time you hear, “That’s not fair,” explain to your children that you’re not attempting to treat them equally. Tell them, “Different people have different needs.” Say, “I address needs. I don’t try to be fair or make things even. Tell me what you need, and we’ll talk about seeing if we can make it happen for you.”

This information was adapted from an article by Chick Moorman and Thomas Haller, two of the foremost authorities on raising responsible, caring, confident children.

Child Abuse Prevention

April is Child Abuse Prevention Month, so I want to talk about how child abuse and neglect continue to be terrible problems. Abuse can be physical, emotional, verbal, sexual, or through neglect. Abuse happens in all cultural, ethnic, and income groups, and it is far too frequent.

In 2012 in the United States, there were approximately 679000 confirmed cases of abuse and neglect. There were an estimated 1,640 child fatality victims, an average of 31 children per week. 77% of child fatalities were under four years old, and over 42% were less than one year old. In 2012 there were 83 deaths in Georgia due to abuse and neglect making our state the sixth worst in the nation for child fatalities. In fact, homicide is one of the leading causes of death among children under age 5 in the United States. In 2012, there were 225 substantiated cases of child abuse in Whitfield County, and 80 in Murray County. In the state there were over 19000.

In April you will see pinwheels on the lawn of city hall in Dalton and the courthouse in Chatsworth. These pinwheels represent the reported cases of child abuse last year. There are far too many. There will be a ceremony at city hall on April 23 in Dalton and on April 28 at the courthouse in Chatsworth. If the issue of child abuse and neglect is important to you, try to attend one of these ceremonies.

Approximately one-third of sexual abuse cases involve children 6 years of age or younger. In the United States, statistics show that as many as one in 6 boys and one in 4 girls are sexually abused before turning 18. In 90% of these cases, sexual abuse occurs in the home or by someone the child knows and trusts. The child senses that the abuse is wrong but may feel trapped by the affection he/she feels for the abuser or fearful of the power the abuser has over him/her, so he/she doesn’t tell.

In school, abused and neglected children exhibit inappropriate behavior in peer and adult relationships, poor initiative, poor language skills, and other developmental delays. Victims of childhood abuse and neglect are at increased risk for alcoholism, drug abuse, depression, eating disorders, suicide, and sexual promiscuity. These children are more likely to be arrested as juveniles and more likely to be arrested for violent crime. More than three-fourths of the prison population suffered abuse as children. Abuse victims are 6 times more likely to abuse their own children.

Based on data from the Centers for Disease Control, the estimated annual cost of child abuse and neglect is approximately $124 billion. Although the economic costs associated with child abuse and neglect are substantial, it is essential to recognize that it is impossible to calculate the impact of the pain, suffering, and reduced quality of life that victims of child abuse and neglect experience. These “intangible losses”, though difficult to quantify in monetary terms, are real and should not be overlooked. Intangible losses, in fact, may represent the largest cost component of violence against children

Child abuse is against the law. Every child has the right to be loved and protected in a safe and healthy environment; and keeping children safe is everybody’s business. Child protective agencies cannot do it alone. As concerned relatives, friends, acquaintances, and neighbors, there are many things we can do to help prevent child abuse and neglect before it ever occurs:

Be a friend to struggling parents. Ask how their children are doing. Draw on your own experiences to provide reassurance and support. Offer to baby-sit, run errands, or just lend a friendly ear to listen. Show you understand. Give them your used clothing, furniture and toys. This can help relieve the stress of financial burdens that parents sometimes take out on their kids.

Be aware of characteristics of families in which abuse may be more likely to occur: families who are isolated and have few friends, relatives, or other support systems; parents who tell you they were abused as children; families in crisis or under a lot of stress (money problems, move often); parents who abuse alcohol or drugs; parents who are very critical of their child and who use rigid discipline; and parents who show too much or too little concern for their child.

Make a donation to an organization that works to prevent child abuse. You can donate money, clothing, food, or toys.

Recognize the warning signs of child abuse. These may include nervousness or fear around adults; aggression toward adults or other children; inability to stay awake or to concentrate for extended periods; sudden, dramatic changes in personality or activities; acting out sexually or showing interest in sex that is not age appropriate; frequent or unexplained bruises or injuries; low self-esteem; poor hygiene; intense anger or rage; being self-destructive, self-abusive, or suicidal; and/or feeling sad, passive, or withdrawn.

If you suspect abuse, it is your responsibility to report it by calling the Department of Family and Children’s Services and giving them the name and location of the child. If necessary, your report will be confidential. If you believe a child is in immediate danger, call 9-1-1.

If you think you are in danger of abusing your own children, there are some simple things you can do. Put your hands behind your back, take 10 deep breaths, remove yourself from the room, or call a friend or relative. You should also join a parent support group, get counseling, and/or take an anger management class.

We cannot allow our children to continue to be trapped in a horrendous situation that maims physically and causes deep and profound emotional scarring that is virtually impossible to completely overcome. We MUST make child abuse prevention a priority. Please do your part to help turn the tide on this insidious epidemic.

Outdoor Play

Parents sometimes underestimate the value of play. In an effort to keep their children safe and help them excel, many parents keep their children very busy in structured activities, academic pursuits, and passive activities indoors. Although reading, homework, and organized arts and sports are all important to a child’s development, so is the opportunity to play outside. Free play is essential in a child’s overall development. It helps children develop creativity and problem-solving abilities; it strengthens their cognitive and social skills; it cultivates initiative and independence; it teaches emotional control; it helps develop motor coordination; and it helps children gain confidence as they explore their world. Play is also a great antidote to obesity, providing physical activity that makes our children strong.

“The earliest forms of physical exercise are a baby and toddler’s simple efforts to explore objects and concepts like space, distance, speed, time and weight,” explains Peter A. Gorski, MD, MPA, the chief health and child development officer for The Children’s Trust. “As children grow, play becomes the vehicle for continued activity, helping to increase coordination, strength, and skill.”

Playing indoors can also be valuable, especially if you provide inexpensive playthings that encourage creativity and self-expression, such as blocks, dress-up clothes, and art supplies. But there is nothing like fresh air and sunshine to bring out the best in your child.

If you don’t take your child outdoors very often, you are not alone. A recent study found that half of the preschoolers in this country do not go outside with a parent daily to play. The study noted that outdoor activity is important to child health and development and that improvement in this area is needed in the interest of our children.

The weather here will be improving with the coming of spring, so plan to takeyour children outside for some fun and games, whether in your backyard, in your neighborhood, or at a park or playground. But even when it’s cold outside, don’t let that prevent you from letting your child play outside. Research has shown, and doctors will tell you, that cold weather does not cause colds or other illnesses. People in cold climates such as Alaska and Canada have no more winter colds or other similar ailments than people living in a warm climate. In fact, cold weather actually appears to stimulate the immune system, according to a study by the Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine.

Letting children play outside is a great strategy if a parent is trying to encourage more physical activity. When prompted to play outside, children naturally engage in physical activities that they enjoy, Dr. Gorski says. “This remains true throughout adult life,” he says. “Ask anyone who has engaged in exercise because they felt they had to, as opposed to folks who pursue an active lifestyle because that brings them pleasure. The former are likely to stop and start repeatedly with unsatisfying results. The latter group weaves physical activity into their lives naturally and playfully as they pursue their favorite hobbies.” If children see play as something fun, they will be much more likely to engage in some form of regular physical activity their whole lives.

The fact that playing outside is so critical to a child’s development is the reason many pediatricians and child development experts are worried about the trend in some school systems across the country to cut back or eliminate recess. Free play outdoors is a learning activity if supervised properly.

The earlier you start encouraging physical activity, the more natural it will be for your children — and the greater the likelihood they will stay active through their teen years and into adulthood.

One of the keys is not to get too serious. It should be all about fun. “Playing together is a great way to keep kids interested in being active,” says Suzanna Rose, PhD, executive director of the School of Integrated Science & Humanity at Florida International University. “We teach parents that they don’t need expensive equipment or a big backyard to play active games. The secret is to make active games and play a part of the child’s daily routine.”